|

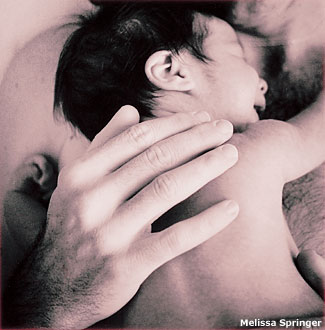

Early Childhood Love and Nurturing

Angela Oswalt, MSW, Natalie Staats

Reiss, Ph.D and Mark Dombeck, Ph.D.

Beyond having their physical

needs for food, water, shelter, and hygiene met, young children also need plenty of emotional and cognitive support, love, and nurturing. Adult caregivers should make it a point to express love and affection for their children every day.

Doing so helps young children

to feel safe, comforted, and included in a warm, bonded relationship. Such feelings of security actually increase children's capacity to learn and to develop mentally and physically.

Caregivers can show love to their children in many different ways. Cuddling, hugging, tickling, or (safely and gently) wrestling can all be used to communicate physical affection. Families can also verbally nurture their children through statements of unconditional love, such as a daily, "I love you."

Reinforcing words of praise

can be offered any time caregivers notice their young children making a positive choice, displaying a new skill or ability,

or being loving towards others. For example, Mom can say, "Jimmy, thank you so much for helping us set the table for dinner."

This statement of praise shows

Jimmy that he (and his behavior) is important to Mommy. Furthermore, he'll start to internalize such affirmations and they will encourage him to engage in helpful behavior in the future.

Love and nurturing can also be shown through thoughtful gestures. Dad can make a point to remember

that Katie enjoys helping him whenever he works around the house. By asking her to join him in building new shelves, Dad shows

Katie that her presence is enjoyed and wanted.

Overall, caregivers communicate

love and nurturing through how they live their own lives. If caregivers keep an upbeat positive

attitude, smile, and stay as calm and patient as possible during difficult situations, they will create a peaceful and positive

environment for their children, young and old.

However, this doesn't mean

that caregivers should neglect appropriate discipline and guidance. Maintaining age-appropriate expectations of children and

setting consistent consequences and privileges based on their behavior will actually help to show children that they are loved in addition to helping keep them safe and secure. More information about disciplining young children can be found here .

It's important to remember that no adults, and especially parents and caregivers, are perfect. Everyone has a bad day now and then. Caregivers

need to expect and to accept that they will make mistakes.

However, if caregivers find

that they are consistently grouchy, irritable, negative, or sad, they need to get assistance to help them be as healthy and

as happy as possible for themselves and for their children.

Depressed or otherwise troubled

parents can reach out to their support system: friends, grandparents, religious group members, neighbors, etc for encouragement and assistance. Sometimes though, talking to friends and family members isn't enough.

If caregivers have symptoms

of low mood, excessive irritability, sleeping or eating problems, or other issues that affect work and interpersonal relationships,

obtaining help from a mental health professional is a good idea. Admitting that you need professional help is not a sign of

weakness. It's one of the bravest things caregivers can do to show their children how much they love them and to model good self-care.

Mental health clinicians in

the United States can be found in our online therapist directory, or by looking up "mental health" in your local telephone directory.

If money is tight and you are worried that you may not be able to afford care, let the agency or therapist know that during

your initial contact. Many mental health agencies and practitioners offer sliding-fee scales (reduced

fees that are based on a family's level of income) to people without insurance or when money is tight.

Beyond showing love and affection, caregivers can nurture young children's growing minds by providing interactive

and stimulating activities. While it may be tempting to allow young children to watch lots of television, especially educational

or age-appropriate cartoons, it's not healthy.

Young children should watch

a maximum of one to two hours of educational television a day. More than this can rob important time away from physical exercise, creative activities, or family time that will help children grow and develop.

In addition, preschool-aged

children are especially sensitive to the effects of media, as they are not yet capable of separating fantasy from reality.

As a result, excessive violence or other intense programs can frighten young children. For more information, see our article

on the effects of media on children and adolescents (coming soon!).

Instead of allowing their

children to watch endless amounts of television, caregivers can read stories, sing songs, play board games, or put puzzles

together with their young children. Children can also use different art mediums such as drawing, coloring, molding clay, or

painting.

Encouraging make-believe games and play, such as dress-up, "auto shop," or "house" can also provide hours of entertainment. Young children

can get their exercise through outdoor games or trips to the playground or park. Furthermore, caregivers can arrange fun trips

to the zoo, museums, or other places where educational and entertaining activities for children take place.

Even though parents often

have busy schedules of their own, they should make it a daily priority to spend time with their families. It's also important in homes with multiple children that each child get some one-on-one time with each parent on a regular basis.

Even unstructured activities

can provide this needed one-on-one time. For instance, allowing children to go to the pharmacy with Mom or sit in the kitchen

while Dad washes dishes can provide an opportunity to share feelings, catch up on news, and laugh together.

The important goal accomplished here is that young children feel included and part of the larger family home. For more information, on

nurturing activities appropriate for young children, see our article on Preoperational Stage Child Enrichment .

source site: click here

Love in Parenting

Love is the first of a three-part formula for parenting: Love, limits, and latitude. Loving children is so important that researchers sometimes call it the “super-factor” of parenting. Good nurturing

makes children feel loved and cherished, and researchers have found that without that feeling, there’s little else parents can do to make up

for it.

Urie Bronfenbrenner, a renowned

expert on child development, says every child needs parents who are crazy about him or her-an “irrational relationship.”

Children are wired to “fall in love” with their parents, and they deserve parents who fall in love back.

Beyond the obvious benefits

of nurturing love, research shows that loving and nurturing parenting is linked to better child behavior at all ages. Nurturing parents build strong bonds with their children, providing them with a sense of security that helps them grow into confident and loving people.

How can you be a more loving and nurturing parent? Here are some ideas:

Learn your child’s

love language. Each person feels love in a different way. A wise parent carefully studies how a child likes to receive love, and then sends love in that way often.

Without this care,

actions that a parent might think are loving can be perceived as unloving. For example, one mother came home from a long day at work, met her little boy at the front

door, ruffled his hair, told him “I love you!” and walked to her room. He followed her and replied, “Mommy, I don’t want you to love me, I want you to play catch with me!”

In another example, a father

invited his teenage son to hunt big game in Montana. The father thought the expedition together would be a great way to spend

time with his son and show his love. But what the son really wanted from his father was less dramatic - he just wanted his dad to go with him occasionally to

a nearby reservoir and watch the ducks take off.

How can parents learn their

child’s love language? One way, according to parent educator Wally Goddard at the University of Arkansas, is simply to notice ways you’ve

already shown love that your child asks for more of.

One father says his children

love their outings with him one at a time. They frequently ask, “When are we going on our one-on-one?” His youngest

daughter is emphatic about wanting to go swimming for their time together. By honoring her request, he shows his love for her in one of the ways she can best receive it.

You can also learn about your

child’s love language by noticing how she or he shows love, according to Goddard. Children often show love in the way they like to receive it. Or you might try recalling when you felt especially loved

by someone and identify what that person did, then treat your child similarly.

You can also take the direct

approach-ask your children what you do or say that helps them feel loved. Answers might

include hugs, bedtime stories, one-on-one outings, midnight pancakes and conversation, playing a game together, or a special

gift.

Have I told you lately…

Keep a record of your loving actions toward your child. Write his or her name at the top of a 3×5 card, then write the following questions and answer

them:

What have I done lately that

really helped Katy feel loved?

How does Katy prefer to receive

messages of love?

What are some different ways

I can send messages that communicate love to Katy in ways she can best feel it?

What will I do this week to

show Katy my love?

Speak kindly to your

children. Compliment their good behavior. Say “please” and “thank you.”

Don’t say anything demeaning or sarcastic.

Even good-humored

sarcasm is easily misunderstood by children and can result in unintended hurt feelings. Instead of saying “Can’t

you leave the dog alone?” say, “Please leave the dog alone.” Instead of saying, “Will you get out

of my way?” say, “Excuse me, I need to get by.”

Express appreciation.

Tell your children how much you appreciate them. Draw attention to their talents and good behaviors: “The table looks

great! Thank you for setting it so nicely.” Or “I can always count on you to help me out. Thanks.”

Write love notes.

Write short notes of love and encouragement. Slip them into your children’s lunch boxes or backpacks. Examples include:

Thanks for helping your sister

clean up her room.

That was a good idea you had

for our family vacation.

You’re special to me.

Will you come with me to the

store when you get home from school? I enjoy having you with me.

Remember the power of

touch. Don’t hesitate to give your child a loving hug, comforting hand-squeeze, or congratulatory pat on the back.

Be a friend. Spend

time playing with your children and doing things with them that they enjoy. If you need to, schedule time with your children

in your planner: “8 pm: Read stories with Rachel,” “2 pm: Go biking with John.”

Declare a love week. Have everyone in your family write down (or draw) what makes

them feel loved. Maybe your first-grader feels loved when you read to him. Maybe your teenage daughter feels loved when you go with her to

the library.

Post the ideas

in the house where everyone will see them. Then, every day for the next week, encourage each family member to do something for another family member that helps them feel loved. Even very small efforts can yield

big results.

For Further Reading:

Between Parent and Child

by Haim Ginnott

Raising an Emotionally Intelligent Child

by John Gottman

Additional Websites

Arkansas Cooperative Extension Service Website - Parenting Journey

http://www.arfamilies.org/family_life/parenting/default.htm

source site: click here

Top 5 Ways to Nurture Gifted Children

By Carol Bainbridge, About.com

"Is my child gifted?" That is the question asked most often

by parents of gifted children. After that question, the most frequently asked question is "How do I

nurture my gifted child?"

Here are five simple answers to that question.

1. Follow Your Child's Lead

What does your child enjoy? What does your child seem to be good at? Provide opportunities

for your child to works with things he or she enjoys or is good at. For example, if your child loves dinosaurs, get books

about dinosaurs, fiction and non-fiction. Get games and puzzles about dinosaurs. Go see dinosaurs at museums. If your child

is good at music or a sport, provide opportunities for him or her to learn an instrument or play a sport.

2. Expand Your Child's Interests

While it's important to provide opportunities for your child to work with his or

her interests and strengths, it is also important to expose your child to new things. Children only know what they have been exposed to, so if they've never been exposed to

music, they may not know whether they like it or are good at it. Children need not be forced to try new things, but they should

be encouraged. It is not forcing a child, however, to insist that they not quit something after two days.

3. Be Creative

This may seem as though it's easier said than done, but once you start thinking "outside

the box," it gets easier. Gifted children love to think and solve problems, so provide them with ample opportunities for doing

so. For example, if your preschooler or kindergartner likes to read, you might write daily notes to pack in their lunch box.

If your child likes science, you might cook together and then ask your child why vegetables get soft when they're cooked or

why cakes rise when they're baked.

4. Look for Outside Activities

Many towns offer classes for children as do museums, zoos, community theaters, and

many universities and community colleges. In addition, most every region has places of historical interest. Some also have

botanical gardens, planetariums, and other places of interest. If you are unsure of what is available in your area, you can

call or visit the nearest "welcome center" for your state or province. They have this kind of information to give to visitors.

5. Keep a Variety of Resources at Home

These resources need not be expensive or elaborate. They just need to allow your

gifted child to develop his or her interests or get exposed to new ones. For example, to encourage artistic talent, all you need initially are simple paint brushes and a paint box, plain white paper, crayons, and other basic

supplies. It's not difficult to create boxes of such materials for your child to use whenever he or she is interested.

The Principles and Philosophy of the 24/7 Dad™ Programs

Maturity requires

mentoring and life-change often happens best in small groups. Small groups are the best contexts for transformation, and that is why NFI created the 24/7 Dad™ programs (A.M. and

P.M.) for community-based organizations. This comprehensive fatherhood program is designed to help men become involved, responsible and committed dads.

The objective of

24/7 Dad™ programs is to support the growth and development of fathers and children as caring, compassionate people who treat themselves, others and the environment with respect and dignity.

The 24/7 Dad™ Christian-based

version shares this horizontal objective but adds a vertical dimension to it. The objective of the 24/7 Dad™ Christian-based version is to help the church equip men to be involved,

responsible and committed fathers, ultimately guiding them into a deep relationship with Jesus Christ.

An objective of the 24/7 Dad™

Christian-based Program is to help all dads cultivate caring and compassionate relationships based on biblical principles. Christian dads can form these relationships with other dads (both men who are Christian and

men who might not know Christ) through small groups.

Through these relationships,

a channel is created to communicate Christian values and ultimately, to help dads develop a deep and meaningful connection to God, through Christ.

The 24/7 Dad™

Christian-based program also provides an extended section of scriptural content that addresses biblical principles surrounding the subject matter of each 24/7 Dad™ small group session.

This content is offered with flexibility in mind so that

you can choose to use scripture that best fits your context.

NFI has taken the

24/7 Dad™ Community-based program and developed a Christian-based overlay for it. We created this overlay to address the specific challenges that churches and Christian leaders face when

trying to reach fathers.

After interacting

with Christian leaders across the United States, NFI determined there was a tremendous need to provide culturally relevant resources, designed to resonate with people who do not yet know Jesus Christ.

The 24/7 Dad™

Christian-based small groups are the perfect tool for continuing

the introduction to Jesus Christ that begins with the 24/7 Dad™ Navigating Fatherhood kick-off seminar and for deepening fathers’ commitment to Christian fathering.

What is Nurturing?

Nurturing is a

critical skill for all the life forms on the planet. For human beings, it is perhaps the single most important characteristic to have for all of us to live in harmony and happiness. Clearly, when nurturing

is not present, it is easy to see how human beings can be

cruel and inhumane.

To nurture is to promote the growth and development

of all of one’s positive traits, qualities and characteristics. To nurture is to respect and care for yourself, for others and for your environment. To nurture is to view the world

and all the people, animals (Prov. 12:10) and things in it as having value

and worth.

Although human life is sacred (Gen. 1:26, 27;

Psa. 139:13-18), all Christians should cultivate a general concern for life in all forms.

Another word closely

associated with nurturance is compassion. Everything Christ did was focused on compassion - it was the very ethos that guided his ministry. In Matthew

9:36, Jesus “had compassion on them, because

they were harassed and helpless, like sheep without a shepherd.”

In the parable

of the lost son, Jesus says, “but while he was still

a long way off, his father saw him and was filled with compassion for him; he ran to his son, threw his arms around him and kissed him” (Luke

15:20). These teachings of Jesus clearly

show the importance of developing a nurturing, compassionate heart as a father.

The apostle Paul

also captured this concept when he said, “Surely you remember, brothers, our toil and hardship; we worked night and day in order not to be a burden to anyone while we preached the gospel

of God to you. You are witnesses, and so is God, of how

holy, righteous and blameless we were among you who believed.

For you know that

we dealt with each of you as a father deals with his own children, encouraging, comforting and urging you to live lives worthy of God, who calls you into his kingdom and glory” (1 Thessalonians 2:9–12).

What is Nurturing Fathering

and Parenting?

Nurturing fathering

and parenting is first and foremost a philosophy that emphasizes the importance of raising children in a warm, trusting and empathic household. It is founded on the belief that a child who is cared

for can learn to care for him or herself and can transfer that caring to others and to the environment.

Nurturing parents not only

act on behalf of the child for the child’s own good, but do so in a way that promotes the child’s overall growth, health and well-being.

The Values

The morals that

are held in high regard and practiced by a society are incorporated into its fabric as values (i.e., the things in life that people consider to be desirable and

worthy). Hence values represent the moral

beliefs that have worth.

To advance the

prevention of father absence, fathers must value the moral beliefs

of caring for oneself, others and the environment, and teach these morals to their children.

The 24/7 Dad™ small

groups rest on the following values:

Value One: A positive self-worth is critical to the ability to nurture one’s self, others and the environment. Fathers who treat themselves with respect will in turn treat others with respect. “Love your neighbor as yourself” - Matthew 22:39b.

Value Two: Empathy forms the foundation of nurturing fathering and parenting. Empathy is the ability to be aware of the needs of others, and

to take positive actions on the behalf of others. “Do

for others what you would like them to do for you. This is a summary of

all that is taught in the law and the prophets” - Matthew 7:12.

Value Three: Fathers empower their children to make good choices and wise decisions

through the use of their children’s strong will and

personal power. Developing a strong sense of personal power is a necessary element in becoming a nurturing individual. “And

now a word to you fathers. Don’t make your children angry by the

way you treat them. Rather, bring them up with the discipline and instruction

approved by the Lord” - Ephesians 6:4.

Value Four:

Discipline is the practice of teaching children to be respectful, cooperative and contributing members to a

family and society. “Teach your children to choose the right path,

and when they are older, they will remain upon it” - Proverbs 22:6.

Value Five:

Humor, laughter and fun promote happiness in families, an optimistic

view of life, an outlet for stress reduction

and the chance to make living together as a family enjoyable. A happy child is

an easier child to parent than a child with a negative, hostile attitude. “A

cheerful heart is good medicine, but a broken spirit saps a person’s

strength” - Proverbs 17:22.

The Principles

The philosophy

of the 24/7 Dad™ small groups is built upon nine principles - natural laws or fundamental truths about fathering and parenting that cut across social, racial and geographic characteristics.

The following information on the 24/7 Dad™ small groups philosophy

will help you as a facilitator understand how fathers will

learn as they participate in the program.

1. Fathering and parenting is a process

that leads to the development of a product.

• Process:

Something that happens; movement; direct action to achieve a product.

• Product:

The end result of a process.

• Examples:

■ An auto

assembly line (process) leads to a car (product).

■ An education

(process) leads to a degree (product).

■ Fathering

and parenting (process) leads to the growth of a child (product).

Processes can be

positive or negative, healthy or unhealthy and lead to positive or negative, healthy or unhealthy products.

2. People learn on two levels: cognitive

(knowledge-head) and affective (feelings-stomach).

• All experiences

impact on the development of Self (our distinct personality and characteristics)

because all “Selves” learn on cognitive and

affective levels.

• Childhood,

defined here as the period of birth to 18 years, is comprised of 157,776 hours that generate a lot of experiences.

• Experiences

can be either positive or negative and impact people on both levels. Positive experiences build Self by providing positive thoughts and feelings. Negative experiences detract from Self by providing negative thoughts and feelings.

School initially

begins as a blend of both levels. Unfortunately, it is often gradually reduced to the sheer presentation of cognitive information.

The result? High disinterest, high drop-out rates and bored learners.

The goal of the

24/7 Dad™ small groups is to present both cognitive and affective learning experiences to stimulate fathers to want to learn.

3. Experiential learning that leads to self-discovery

is the key to learning.

• The experiences

we have during our lifetime form the basis of the perceptions we have regarding our Self.

• Activities

in the 24/7 Dad™ small groups promote self-awareness and self-discovery.

• Growth

as a man will give birth to a nurturing role as a father and parent.

4. Nurturing fathers are born out

of nurturing men.

• A nurturing father is a nurturing man first.

5. Positive self-worth plays a significant

role in becoming a nurturing father and parent.

• Self-concept:

Our self-concept is formed by the messages and thoughts we have about our Self.

• Self-esteem:

Our self-esteem is formed by the feelings we have about our Self.

Together they determine

our behavior. Therefore, behavior is an expression of how we feel and think at any given moment. The goal of nurturing fathering and parenting is to create positive

experiences to build a child’s self-esteem and self-concept.

6. Fathering and parenting is a family affair. To maximize effectiveness, all members must participate in family life.

• A father’s

involvement in the life of his children is affected not only by his own beliefs, attitudes, values and behavior, but by the dynamics that exist within and between his own family and the family of the mother(s) of his children.

7. Fathering and parenting is a role. It

is important not to lose yourself in being a father.

• All people

have a Self. All people play many roles. A role is something a person does in the presence of others or in a specific situation. Saying that fathering is a role does not mean that anyone can step into that role (e.g.,

a mother) and perform it adequately.

There are three

basic categories of roles that parents play:

• Family:

father/mother, son/daughter, brother/sister, husband/wife, aunt/uncle, grandfather/grandmother; etc.

• Professional:

teachers, doctors, lawyers, truck drivers, fire fighters, social workers, etc.

• Community: voter,

neighbor, cub-scout leader, den mother, consumer, etc.

8. Nurturing Self is an important aspect of nurturing children.

• Most people

feel that it is a crime to take time and nurture themselves. This feeling is particularly

true for parents.

• The prerequisite

to being and maintaining nurturing fathering and parenting roles is to take time to nurture one’s Self.

9. Change is evolutionary, not revolutionary.

• Change

is gradual. A father’s adaptation and acceptance of a desired behavior will only occur if that behavior is perceived to hold value by the father. Additionally, as a father’s faith

in Christ deepens, he will want to be the best dad he can

be as a way of expressing his love for God.

source site: click here

The Nurturing

Father

by James Kimmel, Ph.D.

Maternal behavior

in primates has been investigated extensively by primatologists, and no one has objected to the use of the term "mother monkey".

On the other hand, the term "father monkey" is seldom, if ever, used seriously, and most primatologists would probably object

to its use. The term "father" implies a humanlike relationship based on kinship in a monogamous family and is anthropomorphic.

G. D. Mitchell

Paternalistic Behavior In Primates1

Humans are mammals,

which means that they develop initially within their mother's uterus, and after birth are nursed by their mother's mammary

glands. The nurturing process natural to the human species does not end with birth; the

newborns continue their development in relation to their mothers.

Nurturing behavior

by the mother is essential to mammalian reproduction. Males are necessary to create new life, but once a male's sperm has

fertilized a female egg, his biological role in reproduction ends. The fertilized egg in the womb, and the infant after birth,

do not require nurturing from their male parent to continue to live and develop.

In spite of the

fact that males are biologically unnecessary for development of the young, it has been estimated that direct paternal2

care is found in ten % of mammals.3

This figure may

tell us more about the nature of male-female interaction in mammals than about the potential in mammalian males to be nurturing. It is important to the understanding of paternal behavior to recognize that mammalian offspring become attached to their mothers. If the father does not regularly associate with the mother, he

will have no significant contact with the life he has shared in creating.

Male-female

attachment is not the usual case among the mammals. It is more common for them to associate with each other only to mate. In such instances,

there is no paternal behavior, since the father is not present when the babies are born or as they grow to adulthood. In animals

that live in herds, male and female are both part of a group but there is little contact between them. Males are often protective

of the group, but not specifically of their own offspring.4

There

are, however, exceptions to the separate living of male and female. Among some mammals, such as wolves and lions, pair bonds

between male and female are formed. Male and female also live together in animal groups that hunt in packs. In such instances,

males are involved with their offspring.

They

are often protective of their mates and the newborn and help in finding food for the young after they are weaned. It can safely

be concluded that paternal behavior is unusual in mammals, but not unusual in those mammals that are monogamous or form pair

bonds (even if the bond is temporary while the newborn are developing).5

Humans

are also primates. Among the primates, parenting behavior by males is rare. This isn't necessarily because males have less

interest in infants, but because primate mothers generally will not allow males to get very close to their newborn. The males

of many primate species have been known to harm infants. On the other hand, males also display protective behavior toward

mothers and their young.6

The opportunity

for primate males to interact with infants is to a great extent determined by the nature of the group in which they live.

There are a variety of social groupings among the primates. There are all-female and-young groups, all male groups, female

groups, one male and several females, and mixed male-female groups.

Some groups are

loose and open, whereas others are rigid hierarchies. The only consistent relationship found in all groups is the one between

mother and child. The special attachment of infant and mother is not typical of infants and fathers, even when males and infants are part of the same group This does

not mean that males do not display nurturing behavior to the young. They have been observed

to protect, groom, play with, provide food for, and form attachments to them.

Among

several species of new-world monkeys, the male clearly demonstrates nurturing behavior.

The male Titi monkey, for example, carries the infant virtually at all times. The male's behavior toward an infant is similar

to the behavior of mother and infant except for the lack of suckling. Carrying and caring for infants by both parents is common

to the Night monkey of Panama and to the Marmoset. Male and female form pair bonds in all of these species.7

Paternal

behavior is less pronounced among old-world monkeys and the apes. However, males are frequently protective of the young and

playful with them. Baboons display considerable paternal behavior. Among several species of Baboons males carry and even adopt

infants.8

One cannot generalize

to the primate order about paternal behavior. There is too much inconsistency between species and within each species. But,

similar to other mammals, the crucial factor in male paternal behavior in the primates is the association of the mother and

a male companion. Newborn primates become attached to their mothers who nurse them. Unless the father has, or forms, an attachment to the mother; and she to him, it is unlikely that the father will have much contact with his offspring.

Although we do

not know if fathers were always a part of the human family of mother and child, we do know that at some point in our history,

males began to assume a parental role. As Margaret Mead has indicated:

When

we survey all known human societies, we find everywhere some form of the family, some sort of permanent arrangements by which

males assist females in caring for children while they are young. The distinctively human aspect of the enterprise lies not

in the protection the male affords the females and the young – this we share with the primates. Nor does it lie in the

lordly possessiveness of the male over females for whose favors he contends with other males – this too we share with

the primates. Its distinctiveness lies instead in the nurturing behavior of the male, who

among human beings everywhere helps provide food for women and children... Somewhere at the dawn of human history, some social

invention was made under which males started nurturing females and their young... Man, the

heir of tradition, provides for women and children. We have no indication that man the animal, man unpatterned by social learning,

would do anything of the sort.9

It should not be

surprising that the human male, even though he has no biological parenting role, is attached to and nurturing of others who are important to him. The capacity to care for another besides oneself has contributed to our evolutionary success. This is not only a

characteristic of the female of our species, but also of the male.

Nurturing and attachment behavior are not oddities; they are found everywhere in the natural world. Being cared for and caring for others is common to all

the social species. In spite of this fact, the nurturing behavior of the human male is usually

considered something he must learn or something that is imposed on him by his culture.

Margaret Mead believed

that male nurturing behavior was a social invention. This is a common belief in Western

civilization, in which perceives human beings (mothers are a temporary exception)

are perceived as innately unsocial and uncaring of others. The view that the male of our species is not naturally nurturing of his young is widely accepted by scholars who have delved into the subject of fathering.

Most recently, David Blankenhorn has stated:

...fatherhood,

much more than motherhood, is a cultural invention. Its meaning for the individual man is shaped less by biology than by a

cultural script or story – a societal code that guides, and at times pressures, him into certain ways of acting and

of understanding himself as a man.10

Blankenhorn further

points out that:

A father

makes his sole biological contribution at the moment of conception – nine months before the infant enters the world.

Because social paternity is only indirectly linked to biological paternity, the connection between the two cannot be assumed.

The phrase 'to father a child' usually refers only to the act of insemination, not to the responsibility of raising a child.

What fathers contribute to their offspring after conception is largely a matter of cultural devising.11

The belief that

fathering is not a natural role but a cultural invention is supported by the fact that throughout civilization the male of

the species has made babies and then had nothing to do with them after they were born.

Nature has allowed

fathers to ignore their creations by the fact that, unlike females, they do not know when they have made a baby. In addition,

they frequently do not want to know or do not care if they have made one. It is not unusual for individual fathers to have

little or no involvement with their children.

It is also not

uncommon for fathers to be cruel, harmful, and abusive to their children. Although humans are the only primate species in

which fathering behavior is consistently found, it is clear that not all children have grown up having a nurturing father or even any father at all.

Studies of groups

of people living outside civilization have indicated that it is rare for children to have fathers who are absent or who are

not nurturing. In hunter-gatherer societies, both mother and father, as well as other male

and female members of the group, are usually described by anthropologists as indulgent of, and nurturing

toward, all children.

Despite the commonly

held belief in Western civilization that the individual is primarily governed in his behavior by selfish motives and instincts,

that "man is a beast to man", it is much more probable that our prehistoric ancestors were individuals who cared for, and

about, each other. The idea that the human individual is basically selfish and uncaring of others, and that to become socialized,

he must repress and control his self-serving impulses, ignores the human nurturing necessity

and its powerful influence on individual development and group living.

Both male and female

evolved to continue their development after birth in relation to a nurturing mother. The natural

nurturing process does more than keep infants alive. It initiates them into a way of living in which there is someone

who cares for and about them.

Nurtured children

learn that security and satisfaction are found in attachment to another human. For these reasons, sociability and socialization are natural outcomes of appropriate mothering. Our requirement

of mothering is the root of our connection to each other. The mother in her attachment and commitment to her child establishes that human life is about affirming the life of another as well as oneself.

Human males do

not have a biological parental role. But this does not exclude them from developing a nurturing

attitude toward others, and specifically, toward children. They are, in their infancy and childhood, the other half

of the nurturing process natural to our species. We are not a species that must learn to

be social.

Human babies (both male and female) are innately social. They could not live if they were not.

Their sociability must, however, if they are to remain social, be matched by a nurturing mother

and nurturing others.

It is not only

mothers who are mammals. Both males and females become nurturing persons like their mothers

when they are cared for in the mammalian way natural to our species. The fact that human males in all known societies nurture

their mates and children would seem to prove that nurturing behavior is not exclusive to

the female of our species. We can all become "mothers" to others even if we do not have a uterus or produce milk from our

breasts. The fact that human males in all known societies nurture their mates and children would seem to prove that nurturing behavior is not exclusive to the female of our species.

The belief in Western

civilization that the human species is composed of selfish individuals who are chiefly governed by self-interest is not universally

true. It is not the case in many societies living outside civilization.

This is a belief

which reflects the nature of individuals when they must adapt to living in the cultures of Western civilization, rather than

the way individuals evolved to adapt to living in the natural world. Indeed, in the natural world in which we evolved, we

could not have survived as rugged individuals alienated from each other. Our success as a species rested on our ability to

collaborate and share.

The roots of fathering

behavior do not lie in male biology or in their need to pass on their "selfish genes", but in their genetic and biological

need for mothering. How males are mothered largely determines if, and how, they will father.

Without mothering,

there would be no fathering. With inadequate or deficient mothering, the male does not develop

the nurturing attitude that is necessary to be, as an adult, a caring mate and parent. Fathering behavior in the human

species evolved because males, as well as females, developed in relation to a nurturing mother

and nurturing others.

The requirement

of nurturing and its fulfillment through mothering is not enough for the mammalian male

to participate in nurturing his offspring. As we have seen, most male mammals and primates,

in spite of their developing in relation to a nurturing mother, have very little to do with

their young.

In addition to

early positive nurturing experiences, fathering requires the opportunity for the male to

associate with his own young as they are developing. To do so, the human male and female had to become more than sexual partners.

As I have indicated,

humans evolved as individuals who collaborate and share. It is doubtful that our sharing was limited to food and possessions.

We shared ourselves with others and we shared life. It is natural for humans to care for, and about, those with whom we are

involved. That is how our mothers evolved to respond to us for many years after our birth.

Why would males,

as well as females. not identify with, and incorporate within themselves, their mothers' nurturing

behavior? It is entirely possible (based on the attachment, intimacy, and tenderness intrinsic to the mother-child bond) that the adult male and female paired as a mutually nurturing couple long

before the development of the modern brain. Pair-bonding may be as natural to the human species as it is to other species.

Paternal

behavior in all primates requires that the individual male is nurtured by his mother as

he develops and that he has the opportunity as an adult to associate with the young. The human male primate has a third requirement:

his culture must support nurturing behavior by fathers.

Just

as culture can support fathering behavior that is nurturing, it can also encourage fathering behavior that is not nurturing. The latter has certainly been true of the history

of childhood in Western civilization, where harsh and cruel treatment of children, particularly by fathers, has been considered

an appropriate part of child rearing.12

The nurturing

father has been found in all societies living in the natural world. It seems likely that the

nurturing father was a part of all prehistoric cultures and that he is as natural to the human species as the nurturing mother. Indeed, Margaret Mead speculated that we first became human when the

nurturing father joined the original family of infant and mother.13

When we lived in

the natural world, the nurturing father fit our species and the organization of the group.

He was his mother's creation, and in his likeness to, and identification with her, he would have supported his mate's nurturing efforts and been (as she was, and his mother and father

had been) caring of his children. The human child, unlike most other primates, had two

nurturing parents, not just one.

The same cannot

be said when one views the history of childhood in civilization. Civilization brought with it patriarchy, which changed the

relationship of male and female, mother and child, and father and child.

Children still

had a mother and a father, but as natural mothering changed or was eliminated in the patriarchal world, the biological nurturing mother became a relic of the past. By eliminating her from children's development, we

have also eliminated the nurturing father and the nurtured child.

Rather than having two nurturing parents, many children have none.

1 G. D., Mitchell, "Paternalistic Behavior In Primates." in

Perspectives on Animal Behavior. Ed. Gordon Bermant. Glenview, Il: Scott, Foresman, 1973.

2

It is difficult to ascertain fatherhood among the mammals, since females in heat frequently

mate with many males. Therefore, it is best to speak of "paternal behavior" rather than "fathering" when discussing the relationship

of males to the young.

3 Jeffrey

Moussaieff Masson and Susan McCarthy. When Elephants Weep. New York: Delacorte Press, 1995.

4 Carrighar, Sally. Wild Heritage. Boston: Houghton

Mifflin, 1968, page 84.

5 Carrighar,

ibid.

6 Gary D.Mitchell,

"Paternalistic Behavior in Primates." Psychological Bulletin, 1968 399-417.

7 Lloyd de Mause, The History of Childhood. New York: The Psychohistory Press, 1974.

8 Mead, ibid.

9 Mitchell, ibid

10 Mitchell, ibid.

11 Mead, Margaret. Male

and Female. New York: William Morrow, 1967, 188-190.

12 Blankenhorn, David. Fatherless America. New York: Basic Books, 1995.

13 Blankenhorn, ibid.

source site: click here

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Developing Close Relationships With Our Teens

In an era of increased drug

use, teenage pregnancy and youth suicide, it’s little wonder that most parents are very concerned about their teens.

Very often they ask: “How can I protect my teens from these things?” An important key is to develop close, caring

relationships with teenagers.

Teenagers who have close relationships

with their parents are less likely to use drugs, abuse alcohol or become pregnant out of wedlock. These teens are more likely

to adopt the beliefs and values of their parents. Teens who are close to their parents resist peer pressure better and are

less likely to commit crimes.

How do we develop close relationships

with our teens? Here are some ideas from experts in adolescent development.

Be honest. Adolescents are developing their thinking abilities. They want to know the reasons for everything, and they expect

consistency from their parents. They are critical of the parent who is dishonest or two-faced.

Be open. Adolescents want to be able to talk with their parents, but they also need their privacy and independence. The adult-adolescent

conversation needs to be two-sided, with both people sharing their thoughts and feelings. Adolescents want to know if, as

adults, we are struggling over the same concerns they are. If we are doing most of the talking, we’re talking too much.

When it is your turn to speak,

watch your language. Sometimes we talk to teens in ways that say “you

would be OK if . . .” or “we will love you more if . . .”( . . . you

go to church, clean your room, get good grades, etc.).

We order, warn, nag, threaten

and preach to our teens to try to teach them to be more responsible and more sensible. However, this can backfire and actually

encourage our teens to be less responsible and less sensible.

Teens are more likely to be

responsible and follow our wishes if they feel accepted. Speaking politely conveys acceptance. For example, we can say, “I’m

sorry to interrupt you, but . . .” or “I realize you may not want to, but it would help me so much if . . .”

Also,

catching teens doing the things we want and praising them for it fosters feelings of acceptance. For example, instead

of praising them for “a nice report card”, say “You’ve done very well in art and science. You must

really like those subjects.”

Be calm. Adolescents like to try out their arguing skills. If you get angry and yell or scream, this is an ideal time for

them to practice. Avoid getting into power struggles and arguments with your adolescent. If you talk calmly, your child can

see you as in control of the situation.

Set clear and consistent limits. Younger children abide by the rules set down by the parents just because they are rules. Adolescents are more likely

to question the importance of the rule and why there has to be one at all. You should respect your child’s need to have the rule explained.

Take time to explain

why this rule is set and allow time for negotiation of certain rules such as curfew. However, don’t hesitate to say

when something is not open to negotiation, such as riding in a car with kids who have been drinking or taking drugs.

Remember that growing up means

becoming independent. In situations where your child’s well-being is not in danger, you may need to accept that your

child makes choices you wouldn’t have made. Or that your child has behaved in ways that you don’t approve. That’s

independence. Your child may temporarily dress weird or follow a strange hairstyle trend.

Your teen is showing individualism

and independence from you. Try to overlook some of the outside appearances and concentrate on the inner strengths of your

teenager. When teens plan a party, leave the planning to them and don’t interfere unless asked or unless the plans become

unacceptable to you.

Be supportive. Independence does not mean isolation. It means establishing a different kind of relationship with parents, not terminating

it. Almost all adolescents say their parents are the most important people in their lives. Adolescence is a time when you

are needed – when teens are trying to figure out who they really are.

No matter how frustrated you

may feel at times, your teen needs you as a base of support, as much now as during the early years of life.

For Further Reading:

The Ten Basic Principles of Good Parenting

by Laurence Steinberg

You and your adolescent: A parent’s guide for ages 10-20

by Laurence Steinberg

source site: click here

Creating More Nurturing Environments for Children

by Pam Leo

"The sun illuminates only

the eye of man, but shines into the eye and the heart of the child."

– Ralph Waldo Emerson

Given a choice, young children

will usually choose to be in a natural environment. They want to be outdoors, in the fresh air and sunlight, barefoot and

naked, surrounded by grass, trees, and flowers, hearing the birds and the wind, playing in water with sticks and rocks.

If you ask most grade school

children what is their favorite part of school, they say outdoor recess. When children spend time outside where they can run,

jump, climb, swing, swim, and play, they eat better, sleep better and are happier. We all know that children thrive in the

outdoors. Yet we often forget how much the environment can affect a child's mood and behavior.

When children spend too much

time inside breathing stale air, hearing the hum of all the lights, electrical appliances, and the television, surrounded

by synthetic fabrics, playing with plastic toys, eating foods that contain artificial coloring and preservatives, they get

cranky and disagreeable.

Our environment affects us

all and we all have different sensitivities, but children do not have the filters that most adults have acquired. Children

absorb all the sights, sounds, smells, textures and emotions around them.

Environments that meet adult

needs or that adults can tolerate often feel very different to children. The philosophy that "it's a cold, cruel world out

there and children may as well get used to it right now" is completely counter-productive to raising children to be as whole,

healthy, and resilient as possible.

The author, educator, and

one of my personal heroes, John Holt, compared human beings to bonsai trees. If you take a tree seedling and clip its roots

and branches in a certain way and limit its supply of water, air and sun you can produce a tiny, twisted tree. A bonsai tree

is a deformed miniature of the tall, straight tree the seedling had the potential to be had it been given the sun, air, water,

soil and food it needed. And so it is with children. They cannot realize their potential if they are given only a limited

supply of the things they need to thrive.

Children have very little

control over their environment. They must depend on us to keep them safe and to meet their basic physical needs. They must also depend on us to do our best to provide for them the most nurturing physical and emotional environment possible.

When a child's environment

is not meeting his needs or is causing stress, he may not be able to identify those needs or stresses let alone communicate

them with words. Children communicate their stress and their needs through their behavior. A child's behavior is always telling

us something. Acting-out behavior is usually a call for help.

A child's behavior may be

telling us, "I'm over-stimulated" or "I need space to move around." When we tell a child to "stop behaving that way" what

they may hear is "stop trying to tell me what's wrong or what you need." My many years of experience of being with children

has taught me that when we take the time to try to figure out what their behavior is telling us, looking at their environment

is a useful place to begin.

A child's behavior is always telling us something.

If a child melts

down at the grocery store when you tell her she may not have a candy bar, is her behavior manipulation or is it a communication

that she can't handle disappointment on top of sensory overload from the florescent lights and the hum of the refrigeration

units?

If a child continues

to climb over the back of the couch when you have repeatedly told him to stop, is the child trying to get the attention he

needs or is he expressing his body's need for something appropriate to climb on? How will we know when a child's behavior

is a communication of a stress or an unmet need related to the environment?

When we look at

a child's environment to try to figure out what might be causing his behavior, we need to consider every part of it. The air

children breathe, the light they see by, the words and sounds they hear, the food they eat, the water they drink, the feel

of the clothes they wear, the things they play with, and the attitudes and emotions of the people around them all affect how

they grow, develop, think, feel and behave.

There is considerable research

confirming that when children are given what they need to build a solid foundation in the early years, they have more strength

to deal with whatever comes their way later. Children are like seedlings. When we raise seedlings in a greenhouse, in rich

soil with good drainage and provide them the right amount of water and sunlight, and protect them from the wind, they grow

deep roots and sturdy stocks.

When it's time to transplant

them out into the world they will be not only hardy enough to survive, but vigorous enough to thrive. Children are not that

different from seedlings. If we want them to develop deep roots and sturdy stocks so that they will be hardy enough to survive

and vigorous enough to thrive, we must make their home their greenhouse.

The family must

be a rich soil that nourishes them. We must provide them with the water of our love, the sunshine of our attention and our protection from the winds of stress that weaken them.

Providing our children with

nurturing environments is more of a challenge in today's world than it has ever been. Many

children do not live in homes with yards and gardens to explore or in neighborhoods where they can spend hours playing outside.

Even the children who do live in such places often have so many scheduled activities that they have very little time to spend

in their yards and gardens.

Many children are spending

more of their time inside buildings than outdoors at earlier and earlier ages. When children are in school, unless they participate

in outdoor sports, they spend most of their time inside.

Just as children have little

control over their environment, there are many things parents have little control over in our world environment. None of us

alone has the power to end all the crime, violence, hunger, pollution, and injustice in the world. Every day when we step

outside our door, these dangers are still going to be out there. What we do have the power to do is to create home, school

and community environments that nurture and protect our children's potential.

To do this will require that

we make some changes. Many parents already feel stretched to their limit trying to juggle earning a living and just making

sure their children are in a safe environment. We may think we don't have the time or the energy to make the changes we would need to make to create a better environment.

Creating more nurturing environments will actually give us more time and more enjoyable time with our children. Struggling

with children's unmet-need behaviors is time-consuming and tiring. The more time children spend in environments that nurture

them, the more delightful they are to be with.

The few hours we spend putting

up a hammock in the yard or on the porch will give us back many hours of joy and comfort, hanging out in the hammock, telling

and reading stories, cuddling and watching the clouds go by together. Creating more nurturing spaces

will look different for every family depending on what they have to work with. The size doesn't matter.

Even small changes can make

a big difference in our children's lives. Whether we plant a big garden full of flowers or put little pots of petunias on

our stairs, seeing and smelling those flowers will nurture everyone in the family.

So, how do we create more

nurturing environments for children? I spent months researching this idea and a great deal

of time and energy this spring and summer creating a more nurturing environment for the

child in me and for the children in my life.

Have you ever heard young

children talk about how much they love it when the power goes out? Without electricity no one is on the computer or watching

television. The whole family gathers in one room by candlelight and tells stories or plays games.

Our lives today are often

so hectic that many homes feel more like a home base where the family sleeps, showers, does laundry, stores their belongings,

sometimes cooks and eats meals, and watches television. For the first seven years of life children need their home and family

to be their most nurturing environment. Since many young children now spend more of their

waking hours away from home than at home, they need a nurturing home environment more than

ever.

Creating nurturing environments for our children means meeting their physical survival needs of food, clothing, shelter

and protection. Creating environments in which children can thrive means consciously creating warm, loving, sensory rich environments where their physical, emotional and spiritual needs are recognized, honored, and met by their family and their community. It is true that children "live what they learn".

Children absorb and imitate

what they experience in their environment. Their exterior environment molds their interior environment. Just as area is a

product of length times width, human beings are a product of nature times nurture. The potential

children are born with will be limited by or nurtured by their environment. A nurturing environment is one that gives children the security and opportunity to discover themselves and their

world.

In a nurturing environment

the family spends more time gathered around the table than around the television. The family table is where the family is

both nourished and nurtured. Working on projects, drinking hot cocoa, playing board games,

learning to peel carrots and roll out cookie dough, having tea parties and eating birthday cake together turns the family

table into a nurturing "center" where many of the most important, interesting and nurturing

things happen in the home.

A rocking chair is an essential

piece of furniture in a nurturing environment. Children

crave the nurturing of touch. Whether we are soothing a baby or reading stories to a young child, rocking is nurturing

to both the adult and the child.

Children rarely refuse an

invitation to be rocked, especially if it also means hearing a story or a song. The rocking chair should be in the room where

we will use it the most. We love rocking chairs so much we have one or two in almost every room. Outside, a hammock creates

another nurturing place to cuddle, read, sing, tell stories and rock.

Gathering around a fire has

always been a symbol of physical and emotional warmth. Children love gathering around a campfire or fireplace. Even if we

don't go camping or have a fireplace or wood stove to gather around, simply lighting a candle at the dinner table can create

the warm feeling of gathering around the fire.

Another quick, and convenient

source of warmth is the clothes dryer. Imagine how nurturing it feels to get out of a bath and be wrapped in a warm bath towel

and dressed in warm flannel pajamas. One of our favorite warm comforts is the rice pillow you heat up in the microwave to

warm cold feet, sooth aching muscles or just to cuddle up with.

Children love to be in or

near water. Just filling a plastic tub with water and some empty containers provides hours of contentment for young ones.

Whenever we take children to the ocean, the lake, the river, a pool, or put them in the bathtub, we provide a nurturing environment. A table fountain is now in the same price range as a toaster and a fountain brings the

soothing sight and sound of water right into our home. The place everyone wants to sit at our house is in the rocking chair

that faces the wood stove and is beside our table fountain.

When we garden with children

they feel connected to the earth and nature. Children need to touch the earth and feel connected to living things. They love

to dig in the dirt, plant seeds and seedlings and watch them grow. Even if we don't have space for a garden or know the first

thing about it we can still give our children the nurturing experience of gardening.

We can put a seed in a jar

of soil, transplant marigolds into a window box, plant a tree on a child's birthday or measure and record the amazing daily

growth of an amaryllis during the holidays. Any connection to living, growing things creates a

nurturing environment for children.

The living things most children

love to be connected to are animals. Most children dream of having a pet to love and care for. I once read that it is a good

thing for children to have animals to care for - it reminds them that humans are not the only living creatures on the earth.

Children love to feed the ducks, birds and squirrels in the park. Hanging a birdfeeder where children can watch it through

the window is a great way to give children a connection to nature. Even if our living situation does not allow pets, we can

provide children with access to animals through friends, relatives, neighbors and community.

Part of creating nurturing environments is spending time with our children in nurturing places.

With everyone in the family so often going in different directions, it's important that families have places to go together. The local library provides the family with more than books. When we attend story

hours and special activities, the library becomes a nurturing environment for our children.

For many families their place of worship provides a nurturing environment.

One of the most family-friendly,

nurturing environments I know is a local family dance at every second and fourth Saturday.

The dances are taught each time so parents and children can learn them together. There is live music and children dance with

their parents, siblings and other families. Afterward there is a potluck dinner for all the hungry dancers. Parents have as

much fun as the children do - it's great exercise, and a wonderful opportunity to experience community.

As children get older they

have a greater need for the nurturing of community. Parenting never used to be and was never

intended to be a one or two person job. It does take a village to raise a child. Since we no longer live in villages, creating

a community for our children is vital to creating a nurturing environment. The calendar

in Parent & Family is a rich resource that lists many activities and events families can do together.

When we create opportunities

for children to spend time with people who play musical instruments, tell stories, dance, sing, paint, garden, cook, sew,

knit, weave and build things, we provide a nurturing environment for their imagination,

creativity, and self-esteem.

One of the most important

aspects of a nurturing environment is ritual. If we grew up in a family where rituals were

an important part of family life we are more likely to perpetuate rituals in our own family, but even if we don't recall many

rituals, we can create new ones for our family. Lighting a candle at the dinner table, reading at bedtime, having pizza on

Friday night, picking apples in the fall, and carving pumpkins at Halloween become rituals when we do them consistently.

Daily, weekly, and seasonal

rituals give children a sense of security, stability, and belonging. These family rituals become an anchor for children as

they navigate their way through a world filled with inconsistency and uncertainty.

One of the reasons children

love the holidays is the nurturing rituals that accompany them. The things we do with our

children give them more than anything we can ever buy for them. Decorating our home, preparing special foods, making gifts

of love, and attending special services, gatherings, and performances together create the nurturing

environment that families need throughout the year. When we learn to incorporate all the nurturing

elements of the holidays into our daily lives we can keep the spirit of the holidays alive in our hearts and our homes

all year.

Pam Leo is a Parent Educator in Gorham, Maine. She has been a student and teacher of human

development for more than 25 years. She is a mother, a grandmother, a parent educator, childbirth educator, a doula, a feature

writer for Parent & Family, a motivational speaker on parenting and birth, and a sponsor of community education events. Her life work is to

"help create a society in which all parents have the information, resources and support to raise children who can realize

the promise of their potential." For more information on attending or scheduling a workshop for your place of business, visit

her website or write to her at pamleo (at) hotmail (dot) com.

source site: click here

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|